On the TV screen, Paul Robeson, then a young man of 35, stands at the front of a southern Baptist prayer meeting in the 1933 movie “Emperor Jones.”

“Now Let Me Fly,” he sings deeply as a chorus of African American voices offer encouragement to his character Brutus Jones, who’s just landed a job as a Pullman porter. Robeson as Jones has been hired for one of the few jobs with a steady income that were open to Black men at the time.

This was the first Hollywood movie to cast a Black man as the leading character and as a Black man actually playing a Black man. Traditional mainstream entertainment had Black male and female actors in menial roles, and in many instances, white men portraying Black men in blackface.

As Robeson sang in this black-and-white excerpt from the movie, a multicultural audience raptly watched him as part of a new exhibit at the Paul Robeson House & Museum in West Philadelphia. They were sitting in a room on the same floor in the same house where Robeson slept the last 10 years of his life, from 1966-1976. It was the home of his big sister Marian Forsythe who welcomed him during the final years of a long, courageous and tortured life.

The West Philadelphia Cultural Alliance reopened the house on Saturday, June 26, 2021, after a year of closure precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The exhibit is titled “Paul Robeson: His Movies, His Music, His Message,” which is part of this year’s Wawa Welcome America festivities. The exhibit will be on display for tours by appointment for the rest of the year.

More than 100 people showed up to take a journey through Robeson’s personal and social life, despite skies that threatened rain and sunshine that kept them guessing. They came from the Philadelphia region, some learning about the exhibit through Welcome America, others returning after having been on previous tours, and all to hear the extraordinary story of this remarkable man. The real-life Robeson used his singing and speaking voice to challenge systems around the world – including in his own country – that oppressed common people. This country made him suffer for it: His and his wife Eslanda’s passports were denied, adversely impacting his income. He was hauled before a House committee to denounce communism (which he did not); his speaking engagements dried up. He was denounced by a society intent on silencing him.

The Saturday event included a red-ribbon cutting ceremony, food, T-shirts, masks and a step-and-repeat backdrop with a cutout of Robeson as Emperor Jones.

First-floor exhibit

The first floor of the exhibit tells the story of the accomplishments of Robeson’s ancestors and Robeson himself. That history was recounted by Joyce Mosley, historian for the Bustill family on Robeson’s mother’s side. Mosley has been tracing her family history for the last 25 years, back to Cyrus Bustill, who baked bread for George Washington’s troops at Valley Forge during the Revolutionary War.

Her documentation of Bustill’s connection to the war garnered her membership in the Daughters of the American Revolution. Mosley has written a children’s book titled “Gram’s Gift” about the family, whose progeny included participants in the Underground Railroad, the Civil War and voting-rights campaigns.

So, Robeson (pronounced Robe-Son, as he noted in answer to a request in 1933) was destined to be an activist and crusader.

In her presentation, Mosley mentioned Albert Einstein’s friendship with Robeson and Lincoln University outside Philadelphia. Einstein decried racism just as Robeson and spoke out against it. A visitor at the house Saturday recalled a “beautiful” photo of Einstein at the college. In the Robeson house is a photo of Robeson with Einstein, as well as photos of Robeson and a young Julian Bond and the adult Bond signing the Robeson photo.

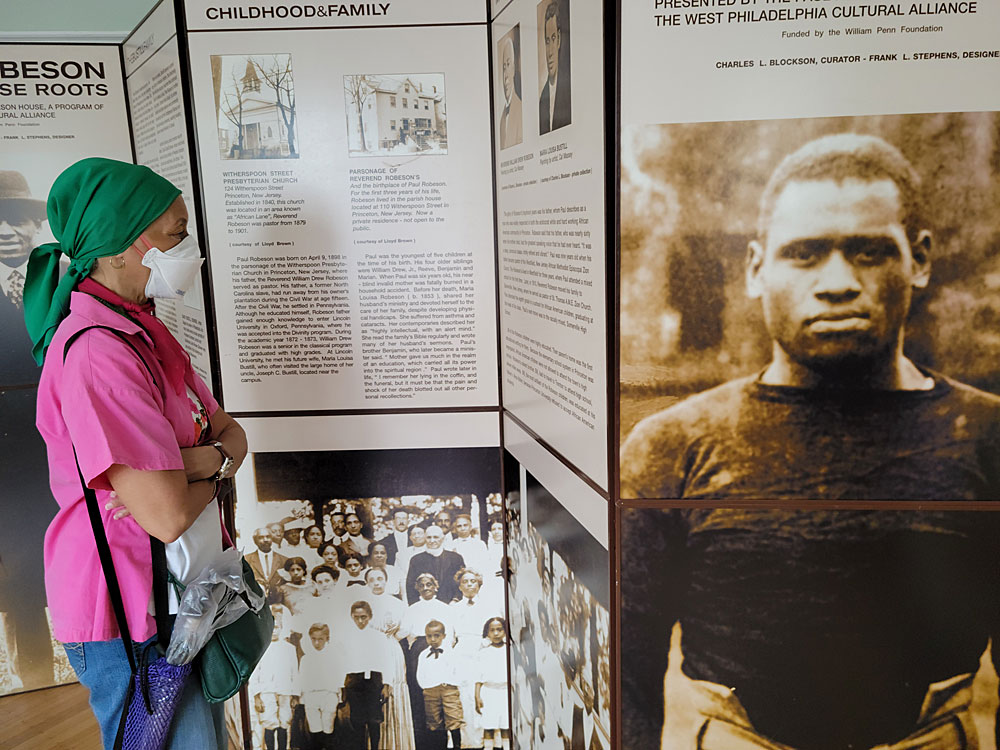

The first floor includes several history panels about Robeson and the family, produced in 1998 by historian Charles L. Blockson and artist Frank Stephens Jr. At Saturday’s event, one of the panels caught the eye of Charlotte Williams of West Philadelphia, who had toured the house before.

She was reading about Robeson’s growing-up years with his pastor father, his mother and two siblings. The children were raised in a home where education was prized and expected.

“This is exceptional,” she said of the exhibit. “Everybody should have the opportunity to see this.”

Second-floor exhibit

The main exhibit is on the second floor, particularly the room where the movie was shown. The walls are layered with photos and other memorabilia depicting Robeson’s life as a singer, and movie and stage actor. Two display cases focus on his major films, “Emperor Jones” and “Show Boat (1936),” and his less-familiar movies.

Visitor John Nolan was particularly interested in Robeson’s affinity for Welsh coal miners. Robeson first became acquainted with them and their cause in 1929 after hearing them singing as they marched through London from their homes in search of government assistance.

Nolan, manager of the Commodore Barry Club, an Irish cultural center in Northwest Philadelphia, says he once showed a series of films on miners in Wales, including Robeson’s “Proud Valley (1940).” He grew up on Robeson’s music, especially his trademark “Ol’ Man River,” through his mother and aunt’s love for his voice. He still has his aunt’s sheet music of a duet from “Show Boat.”

Robeson’s life is “a very moving story,” Nolan said. “He was prohibited from traveling. They took his livelihood away.”

“He was in the Broadway production of ‘Show Boat’ before the movie, wasn’t he?” Nolan asked. The answer was in the exhibits:

The theater wall shows that the prolific Robeson was in “Show Boat” in London in 1928 and the Broadway production in New York in 1932. The movie display case shows that he was in the movie in 1936.

Nolan lamented that the younger generation doesn’t appreciate what Robeson endured or accomplished, especially his involvement in the first transatlantic concert. “It was sold out in Wales,” he said.

A case in the exhibit holds reproduction photos and other memorabilia on that momentous 1957 concert where Robeson in New York sang clearly through underwater cable to an audience in London in his bass baritone voice. He sang a second concert for a Wales audience a few months later.

Robeson’s bedroom on the second floor was off-limits, but visitors could peek inside. Among them were Meshael Jones and her brother Marcelous.

“I live in South Philly, so it’s nice to know a historical museum is here in a neighborhood next to mine,” said Meshael. “It’s awesome to be able to come visit and experience the history.”

Marcelous, who lives in Bucks County, found the experience enlightening, too. This is “very good history,” he said, “to learn the history of Paul Robeson and what he’s done, his accomplishments for the civil rights movement and everything he’s brought to Philadelphia.”

For Deborah Ford, the airiness of the room was powerful, with daylight pouring in through tall windows overlooking the neighborhood in back of the house.

“It’s magnificent. It’s so light and airy and clean, beautiful wood floors, gorgeous sunlight coming in through the windows,” she said. It was a fine place for Robeson “to rest, to contemplate, to think about his

life, to think about the issues that are important to him, what he’s fighting for, who he’s fighting for. Amazing, just amazing.”

She said she learned of the reopening after receiving a Wawa Welcome America brochure. “I used to live in West Philly, and I’d passed by and see the sign, but I never came in. So, this was a great opportunity.”

David Merrill has been a volunteer at the house for about two years. Robeson’s legacy keeps him connected to and in support of it. “Love,” he says. “That’s it. That’s how I feel about it.”