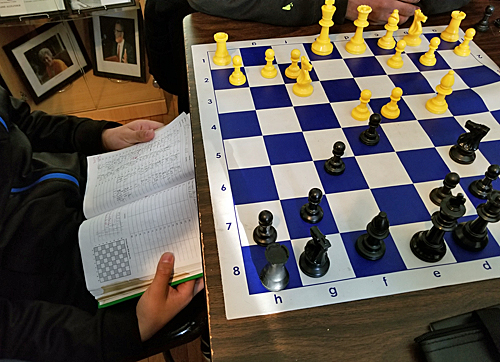

Photos by Sherry L. Howard

The experience was both symbolic and memorable.

Mikyeil El-Mekki had been coaching the Paul Robeson Chess Club for only a few years when he and his team of champions were returning from the national junior high championships in Dallas, TX. The eight African American students had won five trophies.

The students had left the plane and he was trailing behind them.

“By the time I got off the walkway and into the airport, students were surrounded by a group of adults, male Caucasians,” El-Mekki recalls. The adults “were naming different sports, attempting to guess what the trophies were for. The one man, he was a senior citizen, he ran through every sport – soccer, basketball, football, karate. He may even have mentioned bowling.

“The students kept giving him the one-word answer, No. They weren’t giving him any help.

“Eventually, he said, ‘Well, what are the trophies for? And when they said, ‘Chess,’ he yelled (to the) section of the airport where his wife was with another senior citizen. And he said, ‘Oh honey, it’s for chess.’

“They walked over, surrounded the kids. It took us another 15 minutes to disengage from the group. They were asking lots of questions about the trip itself and really congratulating the children on what they had done.

“I realized immediately how that – along with some experiences at the national championships – how chess symbolized an intellectual sport … where we were expected not to be able to participate, let alone excel.”

El-Mekki’s players have continued to win, beating out competitors in state and national championships and bringing home trophies, awards and medals. They’ve mentored other school and club teams.

The makeup of the group has also expanded, with children from a dozen cultures and nationalities represented. “Regardless of race, culture or background, students are able to succeed even at the state and national level,” he says. “The only thing that was missing, particularly here in Philadelphia, was the opportunity to do those things.”

The team practices at the Robeson House & Museum, and some of its trophies sit like shiny gold sentinels on the fireplace mantle and the piano in the front room. The team also practices at two other sites.

Being at the house, says El-Mekki, gives him a chance to tell stories of Robeson’s heroism and determination.

“I use his name as symbolizing black genius,” he says. “The idea that here was this genius, African American genius, who lived right in West Philadelphia among the people, to be able to tell them that these are the rooms he walked in. For me, I’ve always felt a certain comfort in the rooms, particularly the second-floor front room. I get a feeling I can almost feel his presence there.”

Robeson was an advocate for inclusion and an opponent of oppression. He used his voice as a singer, actor and orator to connect people all over the world.

El-Mekki tells the stories of Robeson’s life to teach the students that they, too, can excel in whatever they choose to do. He knows exactly what he wants them to learn from his teachings:

“The inspiration of this genius and the idea that if they apply themselves, put their mind to it, no matter what their background is, education level, sociological, economic background, no matter what culture they come from, that we all are blessed with gifts of genius and character. And if they choose to hold on to that and believe in that, they could accomplish things the likes of which people would not necessarily believe is possible. Just like some of the stories I heard of Paul Robeson.”

Chess has been a part of El-Mekki’s life since he was a young child. His oldest brother Sharif taught him the game when he was 4 years old, and the two played against each other. His parents were members of the Black Panther Party, and they devoted a room in their West Philadelphia home to books. He learned to read when he was 2 years old.

“Learning and the love of learning was something that I inherited,” says El-Mekki. “It was part of the culture I grew up in, part of the community and part of my education. I went to a private school when I was young that was built on community and the idea of helping the community to overcome the oppression inflicted on minorities, specifically African American people.”

Around 2005, before he had even heard of the Robeson house, he formed a chess club with students from two middle schools. He wanted to name it after an “African American freedom fighter,” and considered Malcolm X, Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman.

During a visit with his family, he found himself perusing the books in their library and came across Virginia Hamilton’s 1979 book “Paul Robeson: The Life and Times of a Free Black Man.”

“I was really affected by Virginia Hamilton’s story in her foreword about her father and how he was impacted by Paul Robeson,” says El-Mekki. “From there, it really cemented for me that this was the individual I wanted to name the chess club after … I also learned that he was a chess enthusiast.”

One day El-Mekki gathered up his chess-club students, took a bus and went to the Robeson House for a tour. He did not know that tours were scheduled, not impromptu, but he and his team were welcomed inside anyway. “They just took us under their wing. They welcomed us with open arms,” he says.

That’s when a relationship began between a club and house that shared the name of an amazing man.

El-Mekki says he had always been a casual chess player who knew nothing about the benefits of competitive chess – travel, tournaments, scholarships, trophies. Once he did, he took advantage of them for his students.

The team started going to state and national tournaments and winning trophies (they were already winners at the local level). During their first appearance at the state championships, they won first place, along with awards in other events.

Soon, they started mentoring other chess clubs. Teaching others how to play chess is part of the learning process in the Robeson club.

“As they’re learning they are taught to be teachers,” he says. “They share the knowledge. One of our models is ‘knowledge is more valuable than wealth.’ In the sense of wealth, when you share it, it divides, and it shrinks. But knowledge when you share it, it multiplies, and it increases.”

Being in the space where Robeson lived during the last 10 years of his life and telling the students about him makes the site an even better home for the club.

“Chess is not the foremost reason (for practicing at the house),” El-Mekki says. “It’s a tool for me to talk to the students. This is the path I walk in, to fight against the injustices I see in the world, primarily institutional inequities and racism, a lot of them surrounding the age-old lie from when we were first stolen as a people that we were not as valuable as other races and then the lie that said we were not as smart as other races.

“Anyone who saw (Robeson) was so deeply affected by his charisma and character, his genius. There’s a picture (at the house) of Paul Robeson and Albert Einstein standing next to each other. (The two intellectuals were friends.)

“Albert Einstein culturally represents white genius. We use Paul Robeson (as) representing black genius.”

______________________

For more information about the chess club, call the Paul Robeson House & Museum at 215-747-4675 or email: paulrobesoncc@gmail.com.